A DRAMATIC DECADE

The 1960s were a dramatic decade for the Anti-Apartheid Movement. It had high hopes after the success of the boycott month in March 1960, when hundreds of thousands of people refused to buy South African goods. But the AAM’s new campaign for wider economic sanctions against South Africa was blocked by governments convinced that trade and investment in South Africa were vital to the British economy.

The AAM’s campaign for an arms embargo had wide support, but the 1964–70 Labour government implemented only a partial ban. The Movement extended its campaign for the isolation of South Africa to sport, the arts and academia.

THE RIVONIA TRIAL

The high point of the decade was the saving of the lives of Nelson Mandela and his fellow Rivonia trialists. As the world waited for the judge to pass sentence in June 1964, there was a real chance the ANC leaders would be hanged. In response to a worldwide campaign they were sentenced instead to life imprisonment.

RHODESIAN UDI

In 1965 the white minority government in Southern Rhodesia made a unilateral declaration of independence (UDI). The AAM took up the cause of millions of disenfranchised black Zimbabweans. For the rest of the decade it spent as much energy opposing Labour proposals for a sell-out to the illegal regime as it did campaigning against apartheid.

As a wave of student rebellion swept Europe in 1968, the AAM attracted new support from young people fired by the growing success of guerrilla fighters in Mozambique and Angola and by the attempt by the African National Congress (ANC) and Zimbabwe African People’s Union (ZAPU) to infiltrate Zimbabwe in the Wankie and Sipolilo campaigns.

SPRINGBOK TOUR

The decade ended on a high note with demonstrations against the 1969–70 Springbok rugby tour. Thousands of protesters disrupted play and joined mass marches at games all over Britain. As the rugby tour ended, the campaign to stop a visit by an all-white South African cricket tour took off. In June 1970 the AAM won its biggest victory so far with the cancellation of the Springbok tour.

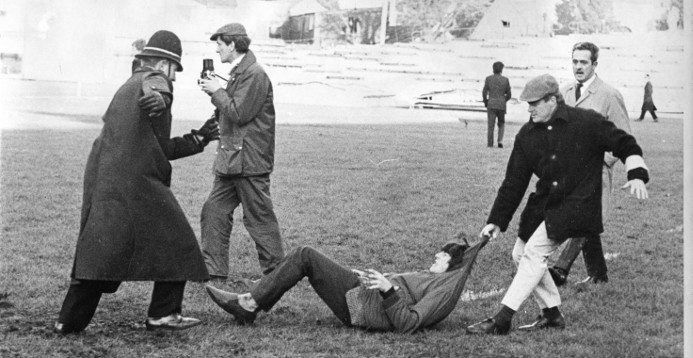

Stewards dragging a protester off the pitch at the Springboks v Swansea rugby match at St Helen’s ground on 15 November 1969. Police turned a blind eye while stewards assaulted demonstrators, many of whom were badly injured. There were demonstrations at all 24 games in the 1969/70 rugby tour of Britain and Ireland.Copyright: Media Wales Ltd

Stewards dragging a protester off the pitch at the Springboks v Swansea rugby match at St Helen’s ground on 15 November 1969. Police turned a blind eye while stewards assaulted demonstrators, many of whom were badly injured. There were demonstrations at all 24 games in the 1969/70 rugby tour of Britain and Ireland.Copyright: Media Wales Ltd

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE ABOUT THE AAM IN THE 1960s

The British Anti-Apartheid Movement was born out of the Boycott Movement in April 1960. After the Sharpeville massacre on 21 March the South African government banned the African National Congress and Pan-Africanist Congress. All paths of peaceful opposition to apartheid inside South Africa were blocked. The liberation movements set about organising an underground resistance, but increasingly they looked for support from overseas. The AAM responded by calling for the international isolation of apartheid South Africa and, together with Christian Action’s Defence and Aid Fund, for support for those imprisoned for their opposition to the white regime.

ECONOMIC SANCTIONS

The first challenge faced by the AAM was to translate its call for economic sanctions into a practical political campaign. South Africa was important to the British economy to a degree unimaginable today. Britain supplied over 30 per cent of South Africa’s exports and was the market for nearly 28 per cent of its imports. It had huge investments in South Africa’s mining industry and nearly every major British company had a South African subsidiary. In spite of Prime Minister Macmillan’s ‘wind of change’ speech, the dominant concern of the 1959–64 Conservative government on South Africa was to protect this economic stake.

In November 1962 the UN General Assembly voted for a trade boycott of South Africa. The AAM wrote to all the countries that voted in favour asking them what action they proposed to take, and to those who voted against the boycott asking them to reconsider. It commissioned detailed research on the efficacy of sanctions and held a study conference to persuade opinion makers. In 1964 it sponsored a major international conference on economic sanctions against South Africa, convened by activist and writer Ronald Segal. The conference was a major event chaired by the Foreign Minister of Tunisia, with delegates from over 40 countries. But it was boycotted by the UK, USA and South Africa’s other major trade partners. The British government showed how seriously it took the conference by setting up a special Cabinet working party to rebut its arguments at the UN. But it was determined to thwart any move, at the UN or elsewhere, to impose sanctions.

SOUTH AFRICA AND THE COMMONWEALTH

A more immediate issue in the spring of 1960 was South Africa’s membership of the Commonwealth. With the Africa Bureau, the AAM organised a high profile lobby of Commonwealth prime ministers. In 1961, after voting to become a republic, South Africa had to re-apply for membership. With the help of Labour MP Barbara Castle, the AAM organised a 72-hour non-stop vigil outside the conference and helped ensure that South Africa was not re-admitted. Its departure opened up the Commonwealth as a forum for pressure on the British government and dialogue between the white dominions and the Commonwealth’s new African and Asian members.

THE UNHOLY ALLIANCE

In January 1962, together with the Movement for Colonial Freedom (MCF) and the Council for Freedom in Portugal and its Colonies, the AAM organised a conference on the alliance between South Africa, the Central African Federation and Portugal. The interdependence of the Southern African region was a central tenet of AAM strategy. It also worked to end South Africa’s illegal rule in Namibia. In 1966 it organised a major international conference on Namibia in Oxford, chaired by Olof Palme, then Swedish Minister of Communications, and with Pakistan’s Foreign Minister Zulfikar Bhutto as the keynote speaker.

ARMS EMBARGO

Britain was the main supplier of arms and military equipment to the apartheid government. Facing an impasse on sanctions, the AAM focused on campaigning for a British government ban on the sale of arms to South Africa. The South African police used British Saracen armoured cars in the shootings at Sharpeville and many people who stopped short of supporting a trade boycott were outraged at the use of British weaponry against defenceless protesters. The Conservative government abstained on a UN Security Council resolution passed in August 1963 calling for a voluntary arms ban against South Africa. It then announced an embargo on weapons that could be used for internal repression. In December 1963 it voted in favour of a further UN arms ban resolution, but it had already discussed an arms deal with South Africa’s Minister of Defence.

Early in 1963 the AAM won its first big success. At a rally in Trafalgar Square on 17 March the Labour Party’s new leader, Harold Wilson, urged the government: ‘Act now and stop this bloody traffic in the weapons of oppression’. He pledged that a future Labour government would impose a total arms embargo. The AAM had high hopes of Labour, but was soon disillusioned. When the Labour Party won the October 1964 general election, one of the first acts of the new Prime Minister was to instruct the Board of Trade to stop arms exports to South Africa. But under pressure from Defence Secretary Denis Healey and a powerful civil service he soon backtracked. The headline ban remained. But existing contracts, including the sale of 16 Buccaneer bomber aircraft, were honoured. All equipment with any possible civil application slipped through the embargo, as did ‘spare parts’, including four Wasp helicopters.

The AAM reacted by lobbying Labour MPs and promoting ‘a more detailed and intensive education of the public’ about life under apartheid. It did this in imaginative ways such as a dramatic presentation in Central Hall Westminster staged in February 1964 with stars Annie Ross and Trinidadian actor Edric Connor. It published a detailed exposé of the gulf between Labour’s pre-election pledges and its performance in office,Labour’s Record on Southern Africa.

Partly as a result of the AAM campaign, when a full-blown crisis erupted on Labour’s arms policy in December 1967, the embargo was saved. In response to pressure on Britain’s balance of payments, leading Cabinet ministers, including Foreign Minister George Brown and Chancellor James Callaghan, argued for an end to all restrictions on South African arms sales. The AAM wrote to the Prime Minister and met George Brown. It lobbied MPs and asked members to send telegrams to Wilson. MPs from across the political spectrum signed a House of Commons motion supporting the embargo. On 18 December 1967 Harold Wilson told Parliament that the arms ban would remain.

BOYCOTTING SOUTH AFRICA

The AAM continued to campaign for a consumer boycott. It circulated updated lists of South African products and asked local authorities to ban Outspan oranges and Cape fruit from their premises. For the next 30 years the boycott was the bedrock of anti-apartheid campaigning activity. Rebutting arguments from the left that the boycott was a soft option, the AAM argued that it ‘created interest when events elsewhere in the world tended to supersede South Africa and [was] a way of involving individuals, actively’1. Over the years, the boycott helped the AAM reach out beyond people who took part in conventional politics. Many people who did not think of themselves as politically involved showed their anti-apartheid commitment by refusing to buy South African products.

At the end of 1962 the AAM extended its consumer boycott campaign to other areas. Its new programme identified sport, culture, films and education as ‘subsidiary fronts in the propaganda war, which can have very far-reaching psychological effects’2. It had high profile successes. In June 1963 playwrights – among them Samuel Beckett, Arthur Miller and Harold Pinter – signed a declaration saying they would not allow their plays to be performed in South Africa. Vanessa Redgrave circulated a declaration to actors asking them to pledge that they would not perform in front of segregated audiences. This was taken up by the actors union Equity. On a visit to London, Marlon Brando endorsed the call for film directors to ban the showing of their films in South Africa. The Rolling Stones broke off negotiations for a South African tour and the Beatles announced they opposed apartheid. In 1965 the AAM asked university teachers to sign a declaration pledging that they would not accept posts in South African universities. A year later it had collected over 600 pledges.

THE RIVONIA TRIAL

On 11 July 1963 the apartheid government arrested Walter Sisulu and other leading members of the African National Congress (ANC) and its armed wing Umkhonto we Sizwe at Rivonia, near Johannesburg. Together with Nelson Mandela, who was already in prison, they were charged with sabotage. There was a real possibility that they would be condemned to death.

The ANC had sent its Deputy President, Oliver Tambo, overseas when the ANC was banned in 1960. He set up an external mission and travelled the world winning support for the anti-apartheid struggle. He now asked the AAM to campaign against the arrests and to set up a special committee ‘with internationally known aims’3. In October the UN General Assembly passed a resolution asking member states to do all they could to press the South African government to abandon political trials.

The result was the World Campaign for the Release of South African Political Prisoners, set up by the AAM, with MPs from the three main political parties as office holders, and composer Benjamin Britten and sculptor Henry Moore among a glittering array of sponsors. The campaign launched a worldwide petition calling for the release of all South African political prisoners, signed by over 194,000 people. It marshalled protests from all over the world – from Belgian, Dutch and Irish parliamentarians, from North Vietnam, Cuba, the Soviet Union, Sweden, the Philippines, the Caribbean and New Zealand. On 9 June 1964 the UN Security Council asked the South African government to grant amnesty to Mandela and his comrades.

As well as sponsoring the World Campaign, the AAM ensured that the South African government was bombarded with messages from Britain. As the trial got underway, it arranged weekly Saturday vigils by writers and actors outside South Africa House. The Committee of Afro-Asian and Caribbean Organisations held a six-day fast on the steps of St Martin in the Fields. There was sympathetic coverage of the trial in the British press. In a prequel to the many honours showered on him in the 1980s, Mandela was elected President of the Student Union at University College, London. On 19 May an AAM delegation met the Minister of State at the Foreign Office to urge the British government to intervene.

LIFE IMPRISONMENT

Immediately after the sentence of life imprisonment was announced on 11 June, 50 MPs marched from the House of Commons to South Africa House and for the next three days hundreds of people demonstrated on the pavement opposite. In centres throughout Britain people showed their solidarity in silent evening vigils. On the Sunday after the verdict, the AAM held a march and rally in Trafalgar Square at which the Bishop of Woolwich called for economic sanctions against South Africa.

The British government had refused to intervene during the trial, but on 18 June voted for a UN Security Council resolution calling on the South African government to free all political prisoners. It then bowed to public pressure and instructed its ambassador in Pretoria to ask for the life sentences to be shortened. When the South African ambassador called at the Foreign Office to denounce this as interference in South Africa’s internal affairs, the Minister told him that, ‘given the strength of feeling in the House [of Commons] … it was in the interests of both Governments that he should have spoken as he did’4.

The World Campaign also tried to save three trade unionists, Vuyisile Mini, Wilson Khayingo and Zinakile Mkaba, who were hanged in 1965, and John Harris, executed the following year. In May 1966 it protested against the sentence of life imprisonment imposed on Bram Fischer, who had gone underground to try and rebuild the resistance networks destroyed in the aftermath of Rivonia.

Paradoxically, the campaign against the Rivonia trial, which marked the suppression of resistance within South Africa for over a decade, helped build the worldwide anti-apartheid movement. In Britain the AAM attracted new members and raised its international profile. The dignified stand of Mandela and his co-accused attracted admiration and sympathy throughout the world. During the trial it seemed likely that they would be condemned to hang. At the time, life imprisonment was seen as a victory.

UDI IN RHODESIA

On South Africa’s northern border, the British colony of Southern Rhodesia was run by a white minority which formed an even smaller proportion of the total population than the whites of South Africa. Southern Rhodesia had formed part of the Central African Federation until Northern Rhodesia and Nyasaland won independence as Zambia and Malawi in 1964. Britain refused to grant independence as long as the country’s black majority were excluded from government. Under Prime Minister Ian Smith the white minority stood firm against any concessions. On 11 November 1965 the Smith government made a unilateral declaration of independence (UDI), causing a crisis for the British Labour government and forcing the British AAM to extend its remit to the whole of Southern Africa. For the next 15 years the AAM spent as much time and energy campaigning on Zimbabwe/Rhodesia as on South Africa.

IN THE WILDERNESS

The early 1960s was a time of hope for the Anti-Apartheid Movement. African resistance within South Africa was still seen as a movement of largely non-violent protest crushed by a brutal regime. Africa was a new and positive force in world affairs. As the economies of its newly independent countries grew, it was expected that they would provide a counterbalance to the West’s stake in South Africa. But by the middle of the decade the vision was fading. In South Africa resistance appeared to have been crushed. Military coups in Nigeria and Ghana and the Biafran war of secession were changing Western perceptions of Africa. In Britain the 1964–70 Labour government was preoccupied with shoring up the balance of payments and was desperate to do a deal on Rhodesia, even if it fell far short of African majority rule.

At the end of 1966 an AAM discussion paper concluded:

After six years of existence, the Anti-Apartheid Movement now has to face a Britain in which disenchantment with African affairs is widespread. The economic crisis is intimidating to proposals for economic sanctions, or indeed any British policy that would threaten this country’s large economic interests in South Africa. Such interest in foreign affairs as there was has increasingly been replaced with a deeply introspective concern with the internal state of Britain5.

RACISM IN BRITAIN

There was also the problem of racism in Britain. The Labour government sent out contradictory signals, passing the first British Race Relations Acts in 1965 and 1968 but trying to bar Kenyan Asians from settling in Britain. Throughout its history the AAM faced the question of whether and to what extent it should campaign against racism at home. In April 1968Anti-Apartheid Newstook a stand on the Commonwealth Immigration Act by publishing an open letter to the AAM’s former President David Ennals, now a Home Office Minister, accusing him of introducing apartheid into Britain. In general though, the AAM took the position that although it was opposed to racism everywhere, it was a single issue organisation that could not initiate anti-racist campaigns within Britain. At a local level anti-apartheid groups often joined in anti-racist campaigns, but the AAM held back from affiliating to national anti-racist organisations.The issue was a perennial one and came up at nearly every annual general meeting.

As in many organisations with their backs to the wall, debate on the way forward became increasingly acrimonious. After it was announced that British ships would take part in joint naval exercises with South Africa in 1967, the AAM’s national committee voted narrowly to ask former presidents Barbara Castle and David Ennals, now Labour ministers, to resign from the government or the AAM. A debate inAnti-Apartheid Newscounterposed parliamentary lobbying to ‘a democracy of the streets’. The discussion reflected the new mood of student and worker militancy about to sweep across Europe, climaxing in the Prague spring and the student insurrection in France.

At the end of 1967 the AAM resolved its debates by agreeing on ‘a shift in the emphasis of our work’ away from parliamentary lobbying towards building:

‘… a powerful political base centring not only on political parties but also on the Trade Union Movement, Youth and Student groups and other militant anti-racist organisations’6.

It recast its sanctions campaign, moving away from set-piece presentations to ‘exposure of the role of individual firms in collaboration with apartheid’ and of ‘trade union investments in South African companies or collaborating companies’7. This was a major strategic shift that opened the way for the initiatives of the 1970s, which took the argument for disinvestment not just into trade unions, but into local government, universities, churches and voluntary organisations.

‘SUPPORT THE FREEDOM FIGHTERS’

By the mid-1960s the liberation movements in Mozambique and Angola were fighting a successful guerrilla war against the Portuguese army. In Namibia the South West Africa People’s Organisation (SWAPO) launched an armed struggle against South African occupation in 1966. The ANC’s armed wing, Umkhonto we Sizwe, was frustrated by its inability to infiltrate its cadres back into the country. In July 1967 it joined with guerrilla fighters from the Zimbabwe African People’s Union (ZAPU) to try to fight its way down through Zimbabwe in what became known as the Wankie campaign.

Support for the freedom fighters fitted with the new mood of militancy within the anti-apartheid movement and wider sections of British society. In Britain, as elsewhere, the main focus of student radicalism was the American war in Vietnam. But some young people, especially from the National League of Young Liberals and UN Student Association, focused on Southern Africa. Towards the end of the 1960s representatives from these groups joined the AAM National Committee, replacing delegates from MCF and the Africa Bureau. They joined with older AAM supporters, including recently arrived South African exiles, to proclaim the primacy of the armed struggle.

With hindsight the huge optimism with which the AAM greeted the Wankie campaign seems misplaced. ‘The armed struggle … has been revealed for all the world to see as the most important instrument for change in the sub-continent’, declared the AAM’s 1967 annual report. It set about trying to win support for the guerrilla fighters, demonstrating under the slogan ‘Oppose Apartheid – Support African Freedom Fighters’ and featuring pictures of guerrillas on the front page ofAnti-Apartheid News. The high point of its campaign was a conference at London’s Round House in July 1969 with speakers from the ANC, ZAPU and MPLA (Movimento Popular de Libertação de Angola) and an analysis by Ruth First of the politics and strategy of guerrilla warfare.

The emphasis on armed struggle was short-lived. The AAM had always been aware that support for guerrilla war would alienate many supporters. Until negotiations in South Africa were clearly on the agenda in the late 1980s, the AAM never diverged from the ANC’s analysis that armed action was an essential part of a multi-faceted liberation struggle. But after 1970 it once more emphasised that the role of a British solidarity movement was to campaign for the isolation of the apartheid regime in order to weaken its capacity to resist. It continued to warn of race war in Southern Africa, but as a threat caused by the West’s failure to rein in South Africa by imposing sanctions. Later, when it publicised the ANC’s sabotage attacks, like the daring raids on the SASOL oil installations in 1980, it presented them as ‘an integral part of the strategy of mass mobilisation’ rather than as the beginning of guerrilla war.

AAM CONSTITUTION AND ORGANISATION

In 1960 the AAM was run by an ad hoc committee made up of South African exiles and representatives of organisations with an interest in campaigning on Southern Africa, such as MCF, Christian Action and the Africa Bureau. In July 1962 it adopted a formal constitution which remained largely unchanged until 1987. This set up a National Committee as the policy-making body, made up of representatives of supporting organisations and up to 30 individual members (from 1966 the individual members were elected by the annual general meeting of members). The Executive Committee consisted of the Movement’s officers and six members elected by the National Committee. This gave representation and a voice to interested individuals and organisations, but provided continuity and a consistent strategy. At the same time the AAM became a membership organisation. Membership grew slowly – from around 1,000 in 1963 to just over 3,000 in 1965; throughout the AAM’s history formal membership never reflected the true extent of support. In the 1960s grassroots support came mostly from students. Labour MP Barbara Castle became its energetic President. She was succeeded by Labour and Liberal MPs David Ennals, Andrew Faulds and David Steel, and in 1969 by Bishop Ambrose Reeves.

The 1962 constitution formalised the AAM’s aims. These were to inform the people of Britain and elsewhere about apartheid; to campaign for international action to bring it to an end; and to co-operate with and support South African organisations campaigning against apartheid. The AAM played a special international role. It initiated campaigns, liaised with anti-apartheid groups in other countries and raised issues in international bodies, particularly the Commonwealth, UN and, in the 1980s, the European Economic Community (EEC). It worked closely with the UN Special Committee against Apartheid. Its constitution committed it to work with all South African organisations opposed to apartheid – the Pan-Africanist Congress (PAC) as well as the ANC. Although the PAC had observer status on the AAM’s National Committee, in practice and especially later on in the 1980s the AAM consulted and campaigned with the ANC.

The AAM received no large grants or government funding and in the 1960s, as later, was financed by membership subscriptions and small donations. From its formation it depended on the dedication of a few staff members who worked long hours for low wages, and on the skills and commitment of volunteers. There was no email or internet – communication was by phone or letters sent through the post. To mobilise supporters for big demonstrations activists handed out thousands of leaflets in shopping centres and transport hubs. In January 1965 the AAM launched a monthly newspaperAnti-Apartheid News, which continued publication until the Movement dissolved itself in 1994.

STOP THE SEVENTY TOUR

One of the AAM’s first campaigns was for a boycott of the 1960 all-white South African cricket tour. Five years later the 1965 cricket Springboks tour was met by demonstrations at every game. The AAM worked with the South African Non-Racial Olympic Committee (SANROC) to ensure South Africa’s exclusion from the 1964 Tokyo Olympics. In 1970 South Africa was finally expelled from the Olympic movement. On a local level there were protests against tours of South Africa by the Welsh Rugby Union and Arsenal Football Club, and students at St Andrews and Newcastle Universities ran on the pitch to disrupt games against the Free State rugby team.In July 1969 a coalition of groups in Bristol disrupted the Davis Cup matches between Britain and South Africa on two separate occasions. On the final day Bristol AA Group organised a march outside the ground and play was interrupted by flour bombs thrown onto the court.

Early in 1969 it became known that an all-white Springbok team would tour England and Wales in the summer of 1970. The AAM wrote to the County Cricket Board and distributed a petition calling for the cancellation of the tour. Then in August news broke that the rugby Springboks would be touring in the autumn. The October issue ofAnti-Apartheid News printed the list of fixtures – 23 all over Britain and two in Ireland. Meanwhile on 10 September a press conference in Fleet Street announced the formation of a new organisation bringing together student and youth groups, including the National League of Young Liberals and the National Union of Students. The new group called itself Stop the Seventy Tour (STST). Peter Hain emerged as its charismatic spokesperson.

The demonstrations against the rugby Springboks were remarkable in a number of ways. They involved a wide range of organisations taking a lead in different places, under the dual umbrella of the AAM and STST. They maintained their momentum for over three months – from 30 October to 2 February – and covered 22 venues all over Britain, from Exeter in south-west England to Aberdeen in north-east Scotland, and in Ireland. While the AAM organised mass marches and sent over 200,000 leaflets to sympathetic groups in every town where a match was played, STST concentrated on a new tactic – direct action.

Direct action was a product of the student militancy of the late 1960s. It had antecedents in the Committee of 100, set up to campaign against Britain’s nuclear bomb. The initiative to disrupt the first match, in Oxford on 5 November, came from young trade unionists at Ruskin College, who formed the appropriately named Fireworks Day Committee. The match was moved to Twickenham, where it was played under siege conditions. STST organised pitch invasions at the Springboks match against London Counties and the international against England at Twickenham. In Swansea protesters were beaten up by vigilantes as the police looked on. Meanwhile the AAM mobilised people of all ages and backgrounds on mass marches. Three bishops joined the march to the Twickenham ground before the England International. Altogether it has been estimated that more than 50,000 people took part in protests against the tour.

As the rugby tour ended, the campaign to stop the cricket tour took off. While the demonstrations against the rugby Springboks had relied on mass marches and militant protests, the cricket campaign went wider, involving organisations representing every sector of British society except business and the far right. The Labour and Liberal Parties and 23 trade unions called for the cancellation of the tour. Britain’s black community mobilised, with the formation of the West Indian Campaign Against Apartheid Cricket. The Chair of the Community Relations Council warned that the tour would do ‘untold damage’ to race relations in Britain. In April both the British Council of Churches and the TUC called on their followers to boycott matches. The ‘great and good’ of British society joined the protests, with the formation of the Fair Cricket Campaign by cricketing bishop David Sheppard. The campaign had an important international dimension. The Supreme Council for Sport in Africa announced that African countries would pull out of the July 1970 Edinburgh Commonwealth Games if the tour went ahead. By mid-May plans for a huge demonstration at the first match on 6 June at Lords were far advanced and STST was warning of militant action. Faced with an imminent general election, the government instructed the Cricket Council to cancel the tour.

CONCLUSION

The decade ended on a high note – with the cancellation of the tour the AAM had won its biggest victory so far. After the high hopes of the early 1960s, the trauma of the Rivonia trial and the disillusion caused by the Labour government’s failure to honour its promises, the AAM entered the 1970s with new confidence. Its aim now was to carry forward its success in the field of sport into the more difficult areas of trade and investment.

- AAM Archive, MSS AAM 43, National Committee minutes, 23 October 1965.

- AAM Archive, MSS AAM 45.

- AAM Archive, MSS AAM 43, National Committee Minutes, 30 July 1963.

- National Archive, FO 371/177072.

- AAM Archive, MSS AAM 70, Memo to Executive Committee, 23 November 1966.

- AAM Archive, MSS AAM 13, AAM Annual Report, September 1967, pp. 12–13.

- Ibid.

CLICK HERE FOR DOCUMENTS AND PICTURES FROM THE 1960s

CLICK HERE TO READ ANTI-APARTHEID NEWS, 1965–69