Political prisoners and their experiences of detention were a key concern of the international solidarity movement. From its early days in the 1960s, AAM activists in Britain led efforts to publicise the imprisonment of political leaders, and in 1973 the Movement played a key role in founding Southern Africa the Imprisoned Society (SATIS), which led campaigns for the release of political prisoners and exposed the deaths of detainees. Attention often concentrated on male prisoners, but female prisoners had their own distinctive experience of imprisonment and devised their own ways of resistance. EMMA WILKINS details her exploration of women’s stories of detention which provided the focus of her recent outstanding final-year dissertation at the University of Bristol.

Uncovering the stories of apartheid’s female detainees

When I visited Robben Island a couple of years ago, I was struck by the hostile glare of the limestone quarry. Decades earlier, the quarry had served as the unlikely home of ‘Robben Island University’. It was difficult to imagine how a group of prisoners had once transformed such a cruel landscape into a place of learning and dreaming. The Islanders mobilised the carceral system against itself. Through the vibrancy of their discussion and debate, they transformed a space that was designed to debilitate them into a space that ultimately kept their spirits alive.

During my visit, women were only mentioned as the wives and daughters of the male Islanders, left behind on the mainland. This reduction of women’s involvement in South Africa’s liberation struggle to their subordinate roles supporting male comrades has been a persistent feature of post-apartheid history-making. Arguably, this has not been more pertinent than in studies of the apartheid detainee. This can be understood as part of a wider disciplinary issue – the existing literature on prison and punishment is dominated by male-centric narratives.

Through my dissertation, I sought to challenge the gendered violence revealed in the historical archive and uncover the lesser-known story of the female prisoner during apartheid. Where was she incarcerated? How did her experience differ from that of a male Robben Islander? And most significantly, how did she resist?

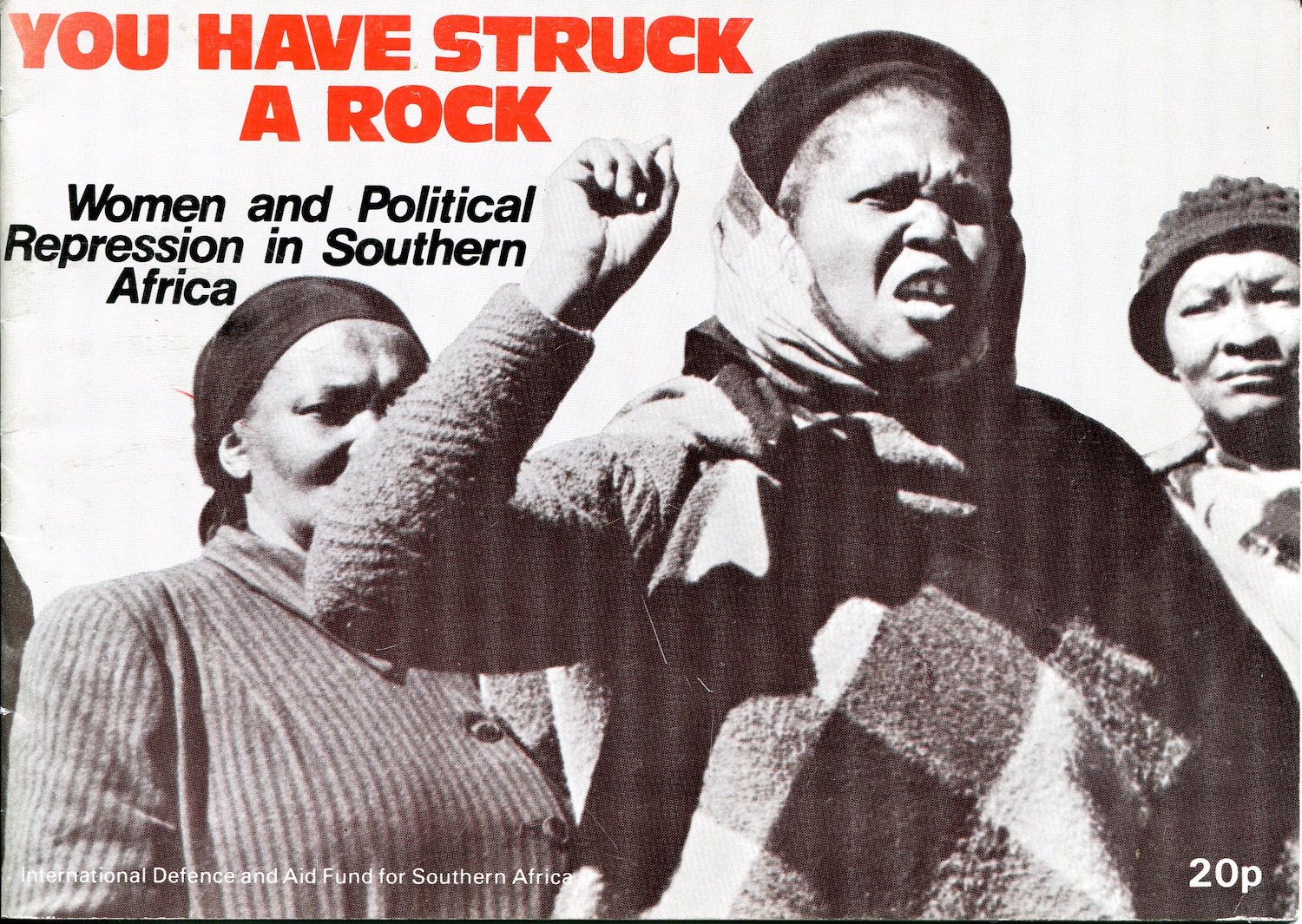

The pamphlet, You Have Struck a Rock: Women and Political Repression in Southern Africa, available on the AAM’s archival website, provided me with insight into the experiences of apartheid’s women detainees. Published in 1980 by the International Defence and Aid Fund, the pamphlet named women who were being detained in South Africa and Namibia at the time: Caesarina Makhoere, aged 23, Deborah Matshoba, detained one week after her wedding day, (Mama) Dorothy Nyembe, the longest serving of them all. The list went on.

I decided to dig deeper into the archive in order to access the voices of these women. I discovered a variety of first-hand narratives – autobiographical memoirs, testimonies given to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, interviews conducted by the South African History Archive. In their narratives, women refuse to be defined by their suffering. Instead, they take the opportunity to present themselves as active agents, operating against the apartheid regime and its oppressive carceral system. By focussing my analysis on female detainees’ expressions of agency and strategies of resistance, my dissertation aimed to honour women’s representations of themselves as courageous and defiant.

Establishing a Collective Identity

In apartheid’s dark interrogation rooms, the security police weaponised women’s relational identities as a tool for their humiliation. Interrogators framed female detainees as worthless and failed mothers who abandoned their children. If a woman had no children, her choice to join the liberation struggle was reduced to her inability to find a husband. These attacks on women’s gendered and political identities were a persistent feature of carceral life for female detainees. Each woman’s sense of self was under constant threat.

In their narratives, women repeatedly highlight the importance of their relationships with others to their ability to survive the brutalities of incarceration. It was through the creation of female detainee communities that women were able to resist the prison authorities’ gendered abuse. Female detainees innovatively discovered ways to communicate between individual cells. They passed notes written in Zulu on toilet paper, listened to the sounds of each other banging on the cell walls, and took it in turns to lead protest songs from their cells. Through written and verbal messaging, female detainees asserted their collective solidarity.

Sharing Knowledge

Whenever they could, female detainees took the opportunity to learn from each other. In ways similar to the Robben Islanders, the space of the prison was used to discuss current events, the history of the liberation struggle, the meaning of being a woman in South Africa. Whether through reading smuggled newspapers or listening to each other’s life experiences, women collectively nourished their political identities and maintained their steadfast devotion to the wider liberation struggle.

At Kroonstad Prison, Dorothy Nyembe embodied the female detainee community’s motherly figure. Mama Dorothy (as she was referred to) taught her fellow younger detainees, including Caesarina Makhoere, about her contribution to the struggle – her role as President of the ANC Women’s League in Natal, her leadership in the 1956 Women’s March against the introduction of pass laws for women, and her experiences in detention. Within a space specifically designed to repress political spirit, Mama Dorothy inspired the next generation of female comrades with her stories.

Showing Compassion

Throughout history, oppressive carceral systems have sought to dehumanise female political prisoners through denying them hygiene and dignity. Apartheid South Africa was no different. In detention centres and prisons, women were forced to wash and dress in spaces where they were exposed to the predatory gaze of security police. Female detainees were unable to access necessities, such as sanitary towels and soap. Many women testify to the utter dread and humiliation of menstruating while they were detained. Sometimes interrogators would force female detainees to stand in front of them with blood running down their legs. This is but one example of the gendered inhumanity female detainees were forced to endure.

Operating against such defeminisation, women prisoners treated each other with compassion. Together, female detainees protected their collective womanhood. They braided each other’s hair, found spare elastic that they could use to make their panties more comfortable, and looked after each other when they were unwell. In her testimony to the TRC, Deborah Matshoba described how when her hair began falling out, her fellow detainee, Jubie Mayet, made her a special mixture and rubbed it gently on her hair. Through caring for each other, female detainees fought to maintain pride in their femininity.

The female detainee community was a space in which women could protect their gender and political identities. It was a space in which each woman could continue to take pride in her sense of self, even in the most hostile of places – the apartheid prison. Through sharing knowledge and demonstrating compassion, women collectively resisted against the oppressive apartheid regime which sought their total debilitation. These defiant female agents deserve to be remembered for their courageous contributions to South Africa’s liberation struggle.

The AAM Women’s Committee regularly campaigned for women prisoners and their stories featured in the Women’s Committee newsletters.