What was it like working for a broke, chaotic, but fiercely committed voluntary organisation in the mid-1980s? SIMON SAPPER was the Anti-Apartheid Movement’s trade union officer from 1984 to 1986. In Parts 1 and 2 of his blog he remembers how he first became aware of apartheid and how he joined the staff of the AAM.

Growing up with apartheid

The struggle against apartheid was certainly my first political memory.

Off we would go, my mum and I, two or three mornings a week to the parade of shops at the end of our street. The bakers were on the corner. The smell was intoxicating, and

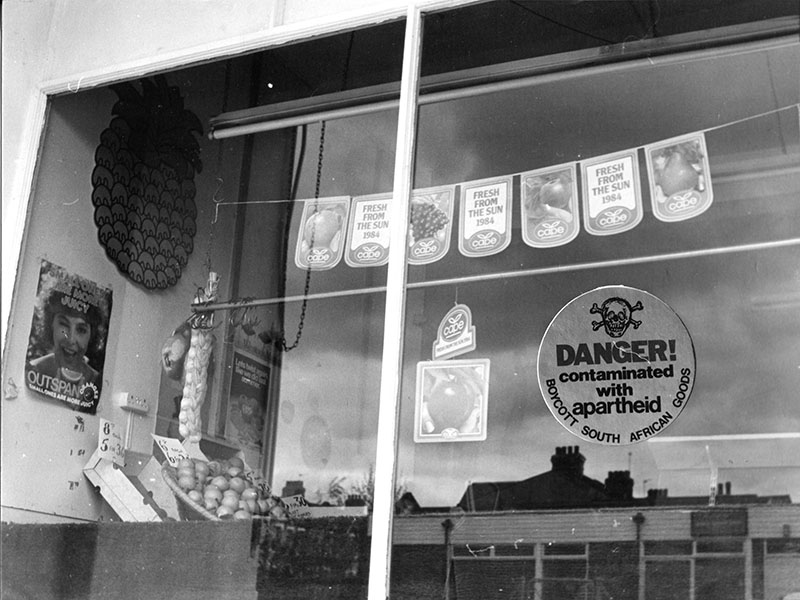

super-fresh bread came in that heavy waxy paper. Next door was the greengrocers. ‘Can we have some of those?’ I asked, pointing towards the brightest and biggest oranges I think I’d ever seen. I was hopefully expecting a yes. But this time the answer was a swift and firm No. Why’s that, I asked? Because they’re Outspan said Mum. This was all gibberish to me. An orange is an orange is an orange, right?

Well, not right, obviously. As Mum explained apartheid and the boycott of South African stuff to me on our walk home, I was dumbstruck. How could anything be so silly, and cruel and wrong? It just made no sense. And my mates at nursery were my mates, irrespective of the colour of their skin.

Roll forward twenty years or so . . .

Graduating from York, which I loved, in 1984, I nevertheless felt a deep need to be back in London. Thatcher was in full flight. Labour’s 1983 election defeat still smarted. I churned out applications like a production line. Bananarama’s ‘Cruel Cruel Summer’ dominated the radio. But then I was offered two very different jobs on the same day.

Cable TV Today was a fledgling magazine for a fast-growing new industry. Offices in Soho and keen for someone who (in theory they thought!) could unscramble the jargon and capture a story. At the other end of the spectrum was the Anti-Apartheid Movement, operating out of a warehouse in the decidedly unfashionable end of Camden Town. They wanted a Campaigns Organiser who knew their way around trade unions.

It was no contest really, apart from one excruciating moment when Mike Terry phoned up from AAM to offer me the job. Mum got to the phone first. ‘I think he thinks the money’s a bit crap.’ (It was, but she really didn’t have to tell them.) Cable TV Today took an article from me on a freelance basis and paid me a week’s worth of AAM wages for my 600 words. And then closed down six weeks later.

It was an extraordinary period, and an enormous privilege. Shortly before I joined, a demonstration of 10,000 people gathered in Trafalgar Square, protesting about the racist injustice of apartheid, the UK’s support for the white minority police state, and calling for anyone and everyone to join the ANC’s call for a boycott of apartheid produce.

It’s a bald statistic, but you’ll get to understand a bit more about what was happening during the two-odd years that I was there when I say that our March Against Apartheid in November ’85 pulled in over 100,000 and the Artists Against Apartheid gig on Clapham Common the following June saw a crowd of 250,000.

It was certainly a time of transition: Prime Minister Thatcher and apartheid President Botha posed for pictures in the garden at Chequers, images which today look as dated but prescient as shots of the Edwardian well-to-do taken in 1913.

A steep learning curve

AAM operated from the ground floor of a two-floor building in Camden. The space and light were great, but a friendly, exiled South African carpenter had built the two toilets and rigged up some rudimentary shelving. The structure was sound – but ‘unfinished’ was the best description that can be given. It was still that way when I left.

But there was a great energy, focus and determination about the place. With my arrival, the staff tally rose to seven. None were southern African, as far as I could tell, but all had a strength of view that drove them. Best of all, it wasn’t in the sometimes over-zealous, suffocatingly evangelistic way that you sometimes get with those who work for causes they are heavily invested in.

If the staffers weren’t South Africans, Namibians, and nationals of other neighbouring states, then our stakeholders most certainly were. I was introduced to those I would work with and ultimately for, the local London representatives of the African National Congress, of the South African Congress of Trade Unions (SACTU) and the South West Africa Peoples’ Organisation (SWAPO) seeking liberation and self-determination for Namibia. And introduced too, to the Executive Comittee of AAM, plus the Trade Union Committee. The southern African network in London was extensive, extraordinarily rich in its stories, skills and backgrounds, and determined.

And on top of all this were those visitors who would be passing through – en route out of South Africa on their way to a safe and eventual destination – and volunteers whose end destination had turned out to be London. At least for the time being.

Often, these people were on the run, literally, from the government or military. National service in the apartheid army was compulsory. And the South African Defence Force was involved many offensive missions – in Angola, Namibia, Botswana, Mozambique. Wars increasingly seen as unwinnable, even by those (or perhaps especially by those) who prosecuted them.

The fusion, or more accurately, interaction that gave the organisation its energy and commitment brought with it some challenges. Crudely, when you are driven by such a deep sense of injustice, by perhaps guilt too, there was no pressure to finish a day’s work at 5 or 6pm – it was your life and you would carry on. I accept that if it is your life, then of course you will carry on. But from the point of view of working efficiently, hard deadlines and better resource management are absolute musts, in my view.

With a number of our southern African friends, counterparts and colleagues, it was difficult to establish trust. And who could blame them. The activities of BOSS, the Bureau of State Security, were justifiably feared. Ruth First’s murder was a recent and still open wound. The people I was working with had endured harassment, incarceration, torture. They had lost friends, family members and comrades. They were keepers of a liberation movement’s secrets. If I was them, I would have been very careful about what I said and to who too.

And, in reality, this was a minor frustration more than an obstacle to getting things done. It was just an enormous privilege to help them in their work, and too easy to forget the back- story.

And this was a live, armed struggle. A visiting ANC official once described it to me like this: ‘If someone is standing on your foot, what do you do? You ask him, politely, to get off. But he ignores you. He stays standing on your foot. He puts all his weight into standing on your foot. “Get off!” you say, very firmly. No response, “Get off, now!” you shout. Until in the end, you have to push him off your foot. That is what we are saying to the Afrikaner: “Get off our feet.” But they aren’t listening or moving so we have to push them off.’

Of course, according to President Botha’s host, the ANC was a ‘terrorist’ organisation.

The other learning point for me was that being a freedom fighter doesn’t make you immune from human frailty or bestow the incumbent with immaculate political views. ‘National emancipation – Yes! Gay rights? Not a prayer’, – the frankness in how this was expressed by the individual (who wasn’t a UK- based officer) whose view it was, was surprising to me. But that was naivety on my part, and not reflective of the opinions I generally encountered.